Honored with the first distinction of historical designation in the City of Phoenix, the Roosevelt Neighborhood has a storied past. From its architectural milestones still visible today, its importance in Phoenix’s original booming tourist trade, and its role as one of the first “streetcar suburbs,” Roosevelt has remained a vital community to our city’s past, present, and future. Discover the neighborhood’s evolution by following the timeline below. (Thanks to Jon Talton, Marshall Shore, and other community members for their research and contribution to this page.)

History

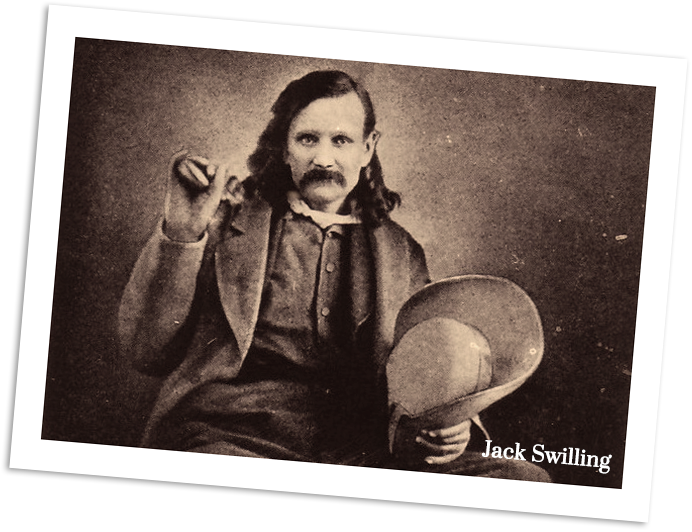

The history of Phoenix traditionally begins in 1867 when John William (Jack) Swilling and a party from Wickenburg settled along the lower Salt River. Swilling organized the Swilling Irrigating Canal Company to construct a series of irrigation ditches by re-excavating the ancient Hohokam canals and to cultivate hay for sale to the U.S. Army at Fort McDowell.

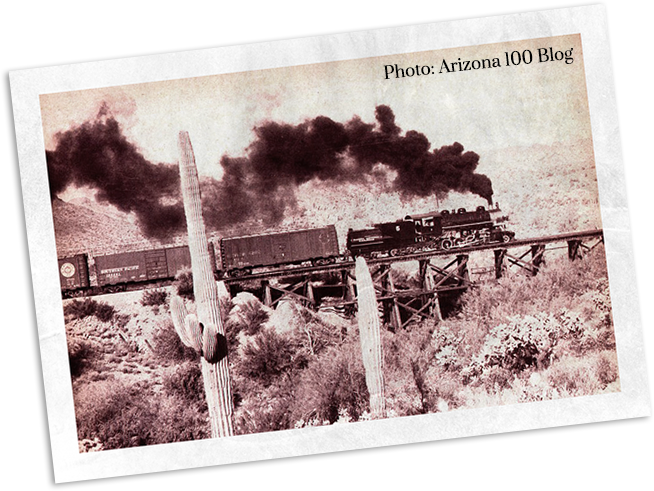

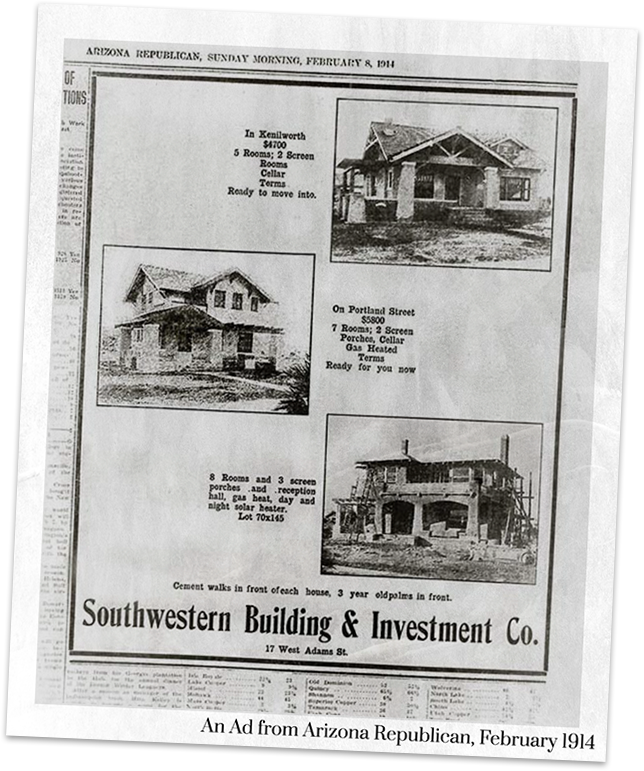

The completion of the transcontinental railroad through Arizona in 1884 contributed to the accelerated expansion of the new city by making processed building materials easily available and affordable. Finished lumber, plate glass, stone, prefabricated components, and pressed and cast metal thus became common in constructing Phoenix’s early buildings. Moreover, after the establishment of a local brick kiln in 1878, builders began erecting brick commercial buildings and residences.

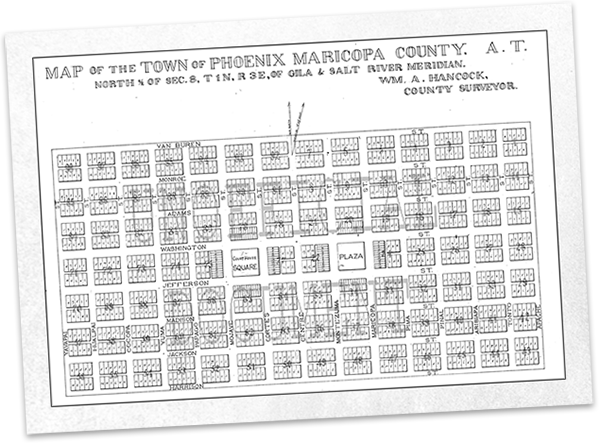

In 1871, the townsite of Phoenix was surveyed and lots were planted by Captain William Hancock. The surveyed area was one mile in length and one half mile in width, containing 320 acres laid out in a north-south grid pattern. The townsite was bounded by Van Buren on the north, by Harrison on the south, and by Seventh Street and Seventh Avenue, on the east and west, respectively.

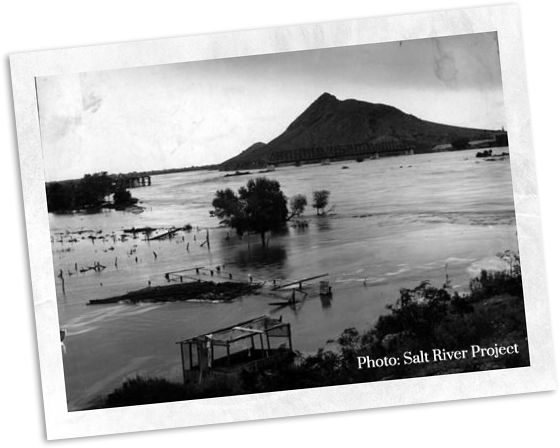

The devastating floods of 1880 and 1891 altered the established growth pattern of Phoenix, an uneven but radial pattern of growth. In February 1891, the Salt River overflowed its banks, covering the lower Valley bottom lands, forcing the evacuation of families to higher ground. Floodwaters came as far north as Jackson Street and as far west as 1st Ave., and threatened residences in the Collins, Murphy, and Linville additions.

As a result of the floods, people left the southern area of the city and its outlying areas and moved to higher ground north of the city along Central Avenue, westward along Washington Street, and adjacent to the Grand Avenue diagonal. This northward movement was a major impetus to the development of the residential additions that constitute the Roosevelt Neighborhood.

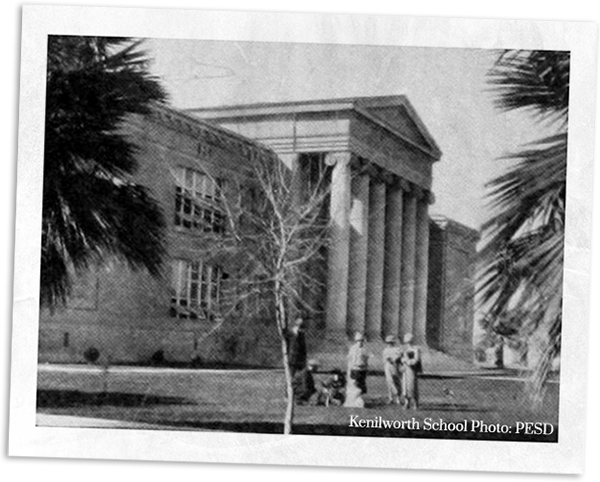

The Roosevelt Neighborhood is significant as a microcosm of the development patterns that shaped Phoenix in the late 19th and early 20th century. The neighborhood was one of the first to begin Phoenix’s northward pattern of development, which continues today. This development was influenced by the proximity of Central Avenue — the primary north-south thoroughfare — and the extension of the Phoenix Railway Line, creating “streetcar suburbs.” Prior to the development of streetcars, Phoenix residents generally lived within walking distance of their places of employment. By 1920, the importance of the streetcar gave way to the automobile. The construction of Kenilworth School in 1920, one of Phoenix’s major elementary schools, also spurred development.

By the end of Word War I, realtors were expressing a need for more housing for new residents and winter visitors. To accommodate this demand, a number of major apartment buildings were erected in the Roosevelt Neighborhood, focused along Roosevelt Street. Post-war prosperity, along with the rise of the automobile as a form of rapid personal transportation made it possible for thousands of American tourists to visit the Southwest. The hotel Westward Ho was one of the first resort hotels constructed to meet the growing demand for luxurious tourist accommodations. Tourism continues to be one of the city’s largest sources of income.

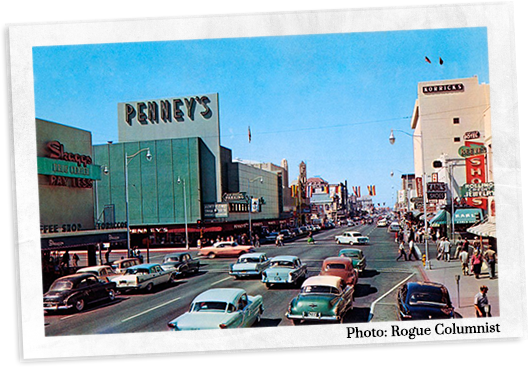

The greater downtown Phoenix area was a cultural and entertainment hub, with shopping destinations like Woolworth’s and Hanny’s and movie palaces like The Fox and The Paramount (now the Orpheum). It was also a major draw for people around the country to come for their health. The dry temperature and clean air were major draws, especially with cool nights and the lack of the urban heat island effect that we have today. Arizona was a relaxing vacation destination, and Phoenix became a winter mecca and a draw for Hollywood celebrities.

To serve the winter visitors and tourists in the Roosevelt Neighborhood, enterprising developers built Gold Spot Marketing Center (corner of 3rd Avenue and Roosevelt St), one of the first shopping centers in Phoenix, built to serve a specific residential area. This marketing center was an early development in a trend that has continued throughout the city’s history, and has had a marked effect on the commercial development of the city. The trend has emphasized the development of smaller neighborhood shopping centers rather than a centralized commercial shopping district.

Architecturally, the Roosevelt Neighborhood has some of the finest examples of early 20th century residential architecture in the City of Phoenix. Among the relatively simple California bungalows, which dominate the landscape, are finely detailed Craftsman bungalows and Period Revival houses (including Mission Revival, Spanish Colonial Revival, Italian Villa Revival, French Provincial Revival, and English Cottage Revival). Many of these are the most notable examples of their styles in Phoenix.

The neighborhood includes important assemblages of vernacular Neoclassical Revival cottages and Prairie school buildings. Trinity Cathedral, Kenilworth School, and the Hotel Westward Ho are also outstanding examples of their building types and styles in the City of Phoenix. The area contained two gems of the City Beautiful Movement, the Moreland Parkway and Portland Parkway. Both were full of lush shade trees and grass, and lined with apartments and Victorian houses.

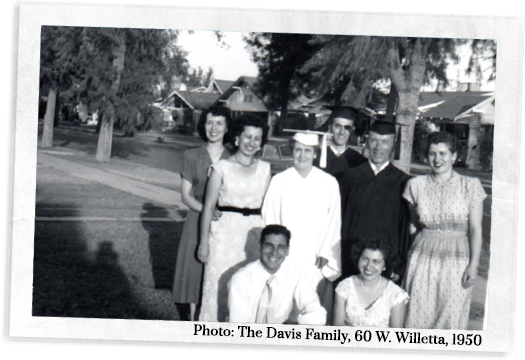

In addition to its importance to the development and architectural history of Phoenix, the Roosevelt Neighborhood was home to much of the city’s elite in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A governor, mayors, city commissioners, Supreme Court justices, doctors, lawyers, and entrepreneurs all made the neighborhood their home. Both Barry Goldwater and Paul Fannin went to Kenilworth School.

The Gold Spot evolved. By the 1960s, it had a Rexall Drugs and Otis Kenilworth’s barbershop, among other shops. Many Roosevelt residents shopped at the A.J. Bayless on the southwest corner of Moreland and Central.

Street cars were replaced by buses in 1948 after the trolley warehouse went up in flames. But the automobile had already taken over — gas was cheap and car ownership ballooned. Development began to scatter, moving northward along Central Avenue into a commercial thoroughfare in replace of the stately homes. You can still some surviving homes in the Old Spaghetti Factory and Ellis-Shackelford House. Anything new became exciting and promising. Downtown quickly faded into the background.

The Roosevelt Neighborhood and surrounding areas began a decline in 1960, when the Wilbur Smith & Associates freeway plan was unveiled. The original plan was to ram a 100-foot-high freeway across the neighborhood. Banks became reluctant to lend where houses were likely to be torn down. Middle-class flight began and Phoenix developed outward away from the core, leaving downtown without a pulse.

The decline was exacerbated in the late 1960s through the 1980s as the city chopped up some of the most beautiful large houses into halfway houses or other social services providers. Defeat of the Papago Freeway inner loop in 1973 gave some breathing room, but city leaders didn’t offer an alternative, such as better transit and connecting I-10 at Durango eliminating the inner loop entirely. Very few Phoenix residents had any reason to visit downtown as the years went on, except for government meetings or court appearances.

With the completion of the freeway, some 3,000 houses, many of the historic, were demolished. Entire streets, such as Latham and Moreland, with priceless bungalows, were wiped out. Only thanks to Mayor Terry Goddard (elected 1984) and urban pioneers were the historic districts rescued. The Episcopalians held on at Trinity Cathedral and held large parcels of land around it.

In the late 80’s and early 90’s, artists saw opportunity where others saw blight and started to create studios in abandoned buildings, planting the seeds for the future Roosevelt Row. The first ever First Friday art walk began in 1994 and the very first inklings of urban revitalization in historic neighborhoods like Roosevelt began.

In November 1983, the historical significance of the Roosevelt neighborhood was officially recognized by the National Register of Historic Places. The state of Arizona has further recognized the neighborhood by establishing Historic Preservation Overlay Zoning in 1986.

At the end of 2008, the Metro Light Rail brought the Roosevelt Neighborhood back to its “streetcar” roots. The Light Rail cuts right through the middle of Downtown Phoenix along Central and 1st Avenue, and connects to West Phoenix, Tempe and Mesa with further pending extensions.

Downtown Phoenix is continuing to experiencing rebirth. The Roosevelt Neighborhood brings character and history to thousands of new residents moving to the area. With local restaurants, coffee shops, bars and the city’s centerpiece parks, this is one of the top areas to live in the Downtown area and will continue on its tight-knit community tradition for years to come.